|

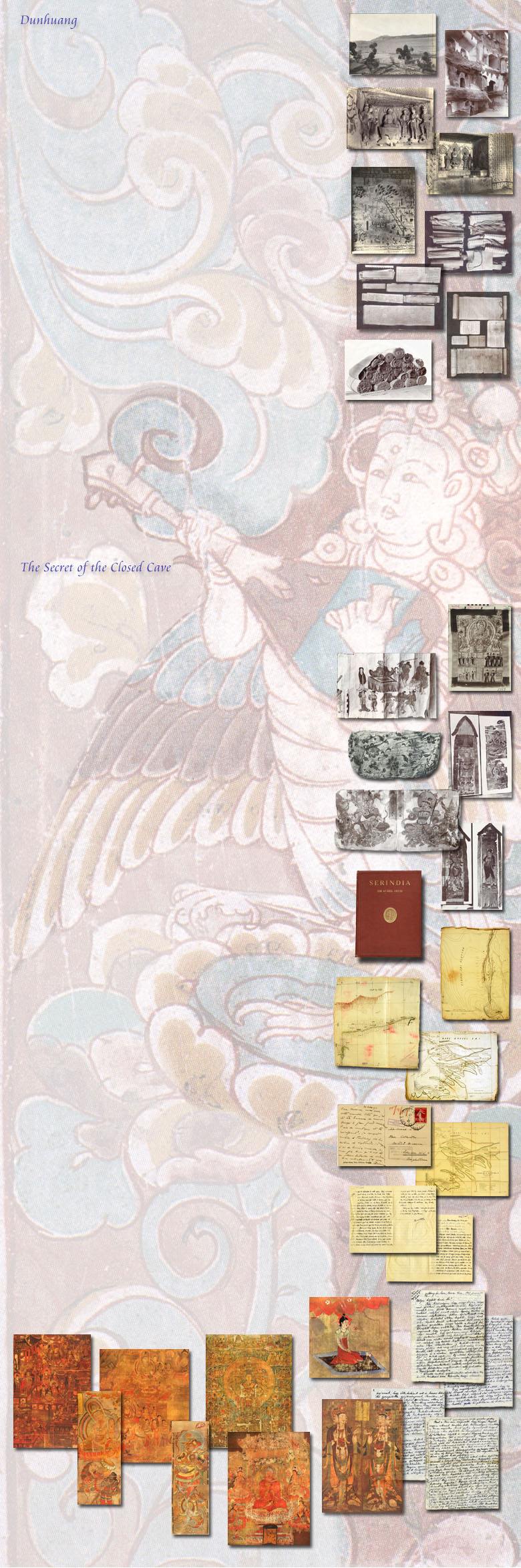

Dunhuang is at the edge of Gobi desert, in the western part of modern Gansu province. This oasis town was not only an important station for the caravans of the Silk Road, but the route of the embassies coming from Central Asia and from India passed through it as well. Missionaries and pilgrims of Buddhism and other faiths took a rest or settled for a shorter or longer period here. The town was founded as a military station by the great emperor of the Han Dinasty Wudi in 111 B. C. in order to ensure China’s western expansion and control of the trade route. A border wall flanked by watch-towers was also built to the north of the town, expanding to the west of Dunhuang as far as the Jade Gate (Yumen). The town later became a center of administration and changed its name: from 622 to the 14th century it was called Shazhou (“Town of the Sand”), but later it took back its old name. Between 786 and 848 it was under Tibetan control, while between 1038 and 1227 it belonged to the Tangut (in Chinese: Xi Xia) Empire. The importance of this site derives from the fact that the road leading to Eastern Turkestan (the modern Xinjiang province) forks here in order to bypass from the south and the north the dreadful Taklamakan desert. By the 4th century A. D. there was a flourishing Buddhist community in Dunhuang. Travelers frequently visited Its sanctuaries before setting out on the dangerous desert route or upon arrival to give thanks for the successful traversing of the sea of sand. To the southwest of the city is the Mingsha Shan, that is the Mountain of Roaring Sand, flanked by a long wall of rocks in which a monk called Yuezun, perhaps in search of a calm place for meditation, carved the first cave in 366. This first cave was followed by many others, almost without interruption, for a thousand years, and while at first they served only as shelters for the monks, later they became decorated temples. This is how the the Cave Temples of the Thousand Buddhas (Qianfodong) originated. This complex of works of art, with its 45 thousand square meters of surviving frescoes and more than 2000 stucco statues found in 492 caves is considered as the most outstanding Buddhist art gallery in the world. |